There is a trash can on fire in the middle of a street. Tongues of flame swell upwards, plastic sags, melts and blackens, and a circle of pavement glows in orange and red in the evening light. It is not a symbolic moment. It is not a metaphor. It is simply a trash can burning, and there are people around who feel its heat, see its glow, and smell its sharp chemical smoke. This takes place in the real world—the world of matter and physics, the world you can burn your hand on if you try to stamp it out.

This world does not last very long.

Someone films it. The moment it enters a phone, the trash can is set loose into the realm of signs. The caption under the clip claims a political group lit the trash can—maybe Antifa, maybe a nationalist militia, or perhaps a disenfranchised teenager. Soon enough the video circulates everywhere, from Reddit threads to Facebook groups, to WhatsApp chats, to news channels. In a matter of hours, the trash can fire is no longer just a fire—it becomes a story.

Jean Baudrillard, the philosopher of late reality, understood something uncomfortable: once a thing becomes a symbol (symbolic), it begins to detach from the world it came from. The trash can that once melted in the street is now a screen-sized icon that has different meanings to different people. It has escaped context, geography, and objecthood. It has become a sign, and the sign has become more influential than the thing itself.

Here’s the first shift: when we watch that burning trash can online, we’re not reacting to a real fire. We’re reacting to what it’s been made to mean. It does not even matter if the caption is wrong, or if the video is mislabeled or deliberately manipulated. What matters is what people feel, what they infer, what it reinforces in them. In this way, the burning trash can is a perfect symbol of the world we now live in: a world where images circulate faster than facts, and often instead of facts.

Now consider the second shift: the story of the fire takes on a life of its own. One side uses it as proof of disorder, lawlessness, or ideological decay. The other side uses it to point out media exaggeration, political opportunism, or manufactured outrage. The event becomes less important than the interpretation. The fire is just a placeholder for whatever you already believed.

At this point, there’s no fire anymore—at least, not one that matters. What matters is the idea of the fire.

That’s simulation. The reality of what happened in the street (who lit the match, who filmed it, how long it burned, what it was made of) has been replaced by something far more durable: the symbolic trash can burning in the imagination of millions of people who never stood near it. Once it’s been framed, posted, commented on, and shared—it becomes more real as an image than it ever was as an object.

This is what Baudrillard calls hyperreality—a state in which symbols, stories, and images no longer refer to anything that exists independent of them. They begin to generate their own truth. Their own logic. Their own consequences. The fire becomes more significant than the fire. It becomes a unit of cultural energy, absorbed into political rhetoric, emotional instinct, and online memory.

Nobody asks anymore whether it happened. They ask what it means.

We live now not in the world of facts—but in the world of framings. The burning trash can is just a convenient vessel. Tomorrow the symbol will be different, but the structure will be the same: something happens, something is filmed, something is explained, and then the explanation swallows the thing. The map doesn’t just represent the territory. It replaces it.

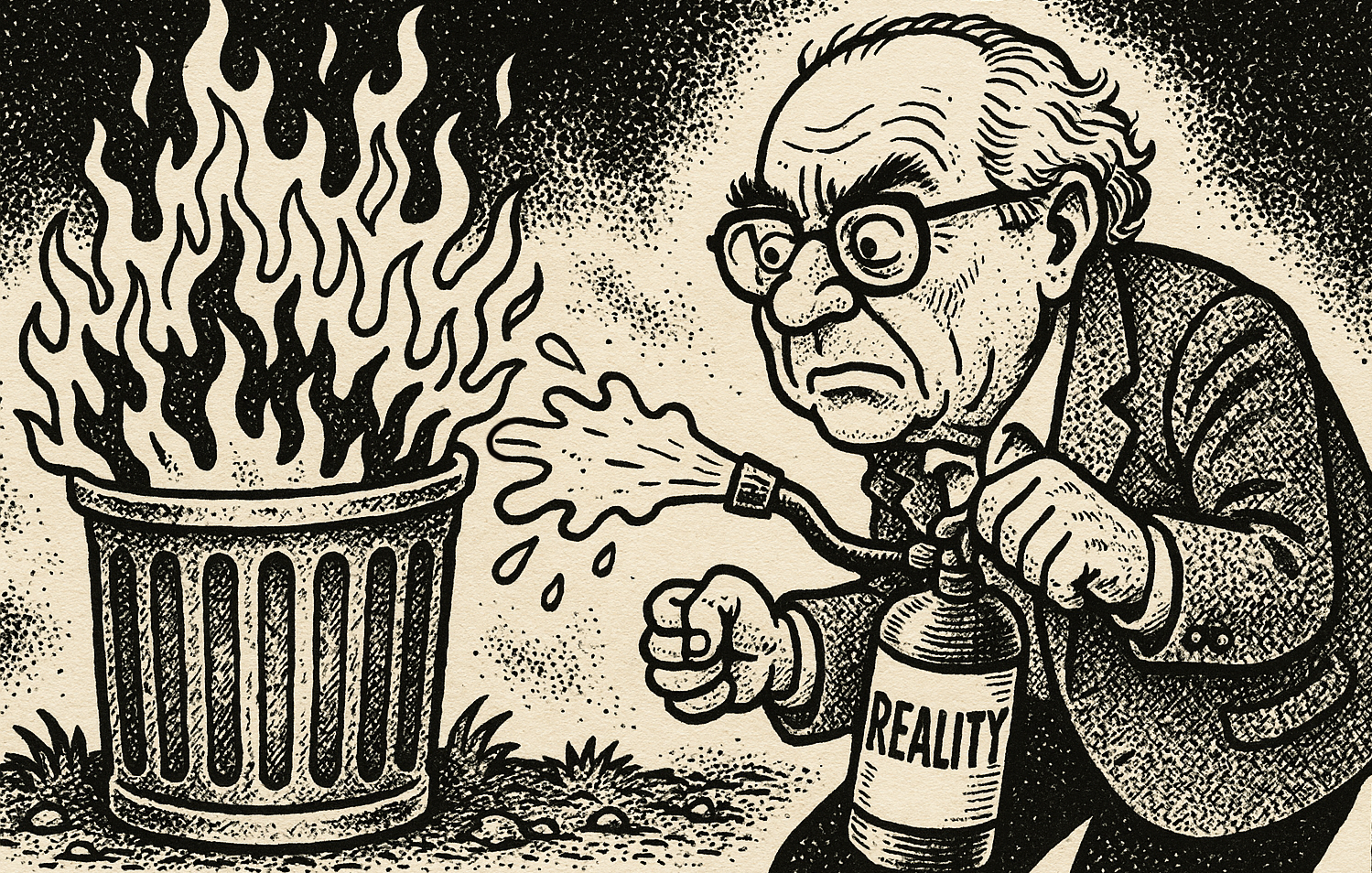

The world still exists outside (of screens*)—but fewer and fewer of us live there. The real fire went out. But the one that lives in our minds burns longer, hotter, and without any possibility of being put out—because it no longer depends on oxygen. It depends only on belief.

Step 1: The Real Event It starts simply enough.

A trash can is actually set on fire. Flames flicker, plastic melts, smoke rises, and a chemical smell fills the air. A real, physical event in the world. People nearby can feel the heat, smell the burning trash, and maybe act to put it out. In Baudrillard’s terms, this is the real—something that exists whether or not we represent it or care about it. For a brief moment, there is no story—just matter, combustion, and sensation.

Step 2: The Representation Somebody films it.

They post a video with a caption: “Antifa set a trash can on fire in town today.” and now something changes. The fire has stopped being just fire—it’s a message, a symbol, packaged with a label and a motive. It may or may not be accurate, but that barely matters. The representation has begun. The event has been framed. The trash can fire has now become an object in discourse—a talking point. In Baudrillard’s terms, this is the image as distortion. It reflects something real, but selectively, through someone’s lens—political, emotional, or otherwise.

Step 3: The Simulation The copy replaces the original

A day later, that burning trash can is now being debated online. Some people swear its / it’s proof of lawlessness. Others say it is fabricated. Still others don’t care who lit it—only that it confirms what they’ve believed all along. The fire continues spreading—but now only as an idea. The real, physical fire is long gone. What survives is the story of it, retold and reshaped by thousands of people who never saw it, never smelled it, never stood near it. This now becomes the simulation, where the copy replaces the original and the event has become secondary and all that matters now is how it circulates*.

Step 4: Hyperreality Symbols no longer point to things that exist.

This is where things get truly unsettling. Once the symbol of the trash can fire becomes powerful enough—once it’s been retweeted, memed, politicized, and mythologized—no one needs real trash can fires anymore. The idea of them is enough and the politicians can (will) say that antifa is burning down cities and news commentators can say that we are currently under attack and people wiill believe what is being said - this is becasue the simulated world of signs and symbols has become more real, more vivid, more emotionally impactful — and in all honesty more interesting than any physical street corner or burning trash can ever could be.

This is hyperreality. A world where symbols don’t point to things that exist. They replace them and the burning trash can has becomes a kind of ghost: a flickering, smoldering heap of meaning untethered from the world.